😷 Festivals as cities; festivals as test case

Can music festivals become testing grounds for how cities can deal with the Covid-19 pandemic?

When Live Nation announced their 98% losses for Q2 2020, Michael Rapino said:

“Our expectation is that live events will return at scale in the summer of 2021, with ticket sales ramping up in the quarters leading up to these shows.”

Last week, I wrote about how we should face the reality that 2021 likely won’t offer this salvation for live events, and definitely not for a regular festival season. Evidence in this regard is Bonnaroo, which usually takes place in June, announcing that they’ll postpone the festival until September 2021. Moreover, the organisers hope that Bonnaroo will be ‘one of the first major large-scale music events to take place post-pandemic.’ Coachella appears to be hot on the heels of Bonnaroo to reschedule (again) to fall 2021 as well.

And yet

That’s the situation in the US, and the pandemic is behaving differently in various places across the world. In the UK, for example, The Guardian has shown that festival organisers, especially for smaller festivals, are moving to make their events happen in 2021. They’re looking at a host of tools to ensure safety, such as thermo scanners, interactive wristbands that vibrate to mark a lack of social distancing, and rapid on-site testing. One of these smaller festivals is Supersonic, who usually host around 1500 attendees making it, perhaps, easier to navigate regulations. In the words of Supersonic organiser Lisa Meyer:

“As a small festival we have the ability to be fleet of foot and opportunistic, so we will reshape the festival within whatever boundaries we have to work with.”

For bigger festivals this is more problematic, with major headliners perhaps not able to put on an international tour. Moreover, more people together on one festival terrain means more difficulty in regulating behaviour. But there might be an opportunity to flip that difficulty on its head.

The festival as a city, the city in the pandemic

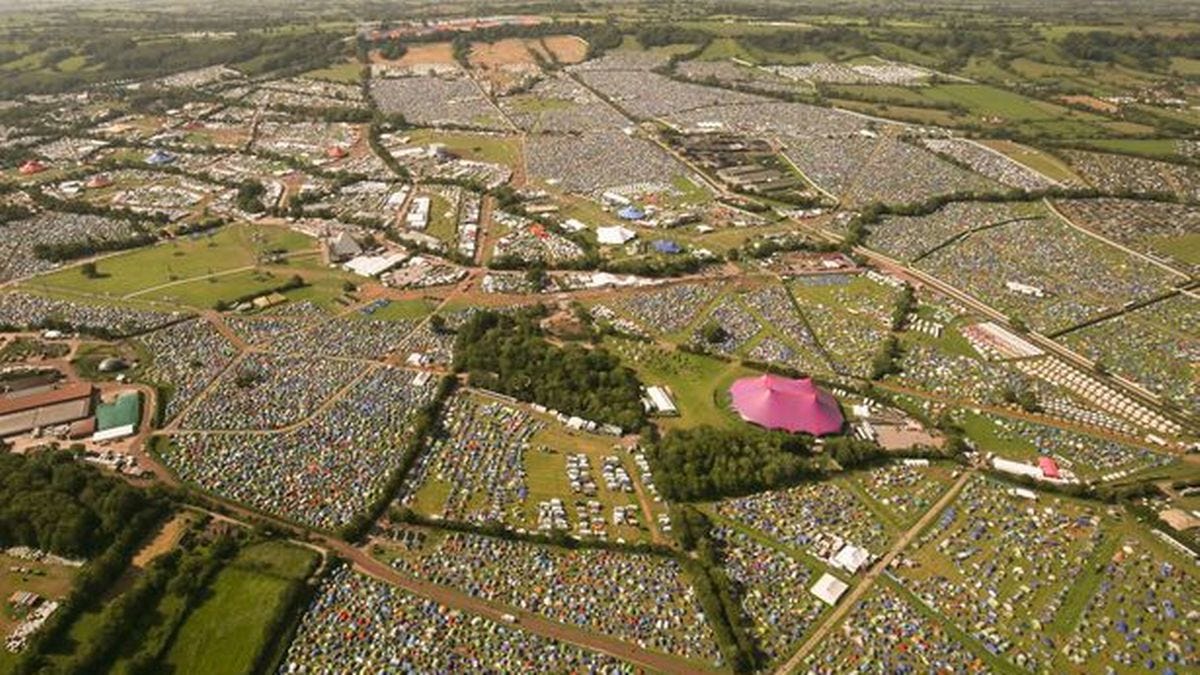

Reading that article in The Guardian I remembered how Dutch festival Lowlands becomes a temporary city with such ‘boring’ city needs as sewage. And its cities that have faced the most difficulty on containing the outbreak of Covid-19, from India to Europe. What’s more, within these major cities, it’s actually smaller and often marginalized neighbourhoods who suffer most. Within such a major city, think Paris, New York or Mumbai, a smaller neighbourhood’s number of inhabitants compares to the number of attendees at a major festival.

The OECD has placed cities at the forefront of tackling the current pandemic. Their Cities Policy Response has 10 key lessons from the current crisis aimed at cities coming out of the pandemic as green, inclusive, and smart places. I want to highlight one of these lessons here: ‘the need for place-based and people-centred approaches.’

The festival as testing ground

Concerts have already provided testing ground for dealing with pandemic-related restrictions in the UK, Germany, and Spain. All of these involved strict hygiene concepts, routing, testing, and social-distancing measures. We could apply these to the festival site, starting with travel and moving through various models on site before sending people home again. However, instead of focusing on things like spectator behaviour the festival as city can allow researchers to discover how to create accessibility. Thinking about basic needs such as amenities and services we can imagine the festival as a place to test how a large group of people can access not just simple things like water, but also regular testing, masks, etc.

Thinking a step further, a festival can also resemble the 15-minute music city. In this idea, Shain Shapiro posits that by encouraging music production cities can become more inclusive and provide a thriving cultural ecosystem. Festival, then, can go ahead in 2021 as places to test how to restrict the spread and respond to outbreaks of Covid-19 in cities. In addition, they can also provide a kind of blueprint for urban planners to bring cities out of the pandemic in such a way that there is a higher focus on accessibility in cities’ recovery strategies.

Quick

A roundup of news and perspectives on the pandemic and the music industry.

David Turner asks if anyone wants to save the live music industry? (Penny Fractions)

A new trick in the list of how to get live events back: The O2 [Arena in London] has purchased electrostatic foggers to deliver a charged anti-bacterial spray across the venue that will envelope all surfaces, providing protection for up to 30 days, with a heightened cleaning regime before, during and after the event. (Pollstar)

On Tuesday it looked like the US stimulus bill with federal aid for the live entertainment sector went through, but it hasn’t yet: Indie venues devastated after Trump kills stimulus talks: 'This is real. We need help' (Billboard)

I strike a note of hope in the artice above, but others are more in the mindset I was at last week: Well this sucks: Recording in the time of Covid (Tape Op)

“One reason to focus on recording regards the clusterfuck that is live music. We don’t have a complete view of the future state of live shows, but they’re not coming back. Not in the way they used to be, and not for a much longer time than most of us will admit to ourselves.”

Cars began to arrive. A man holding some traffic cones directed me to park facing the church and the choir’s boyish conductor, Mike Pfitzer, who stood under a small tent. He looked down on the 30 cars parked below like a preacher delivering a sermon. Kathryn came up to each window and handed out sanitized microphones from a bin — like burgers and shakes at a drive-in.

Music

For inspiration this week I listened to Antoine Berjeaut & Makaya McCraven’s Moving Cities record. Back in 2019 they described the music as ‘echoes of the recent evolution of international metropolises constantly torn between individualism and collective endeavours, in a disrupted geography.’ It’s also just seriously tightly played jazz!

MUSIC x CORONA is composed by Bas Grasmayer and Maarten Walraven.

❤️ musicxtechxfuture.com - musicxgreen.com - linkedin Bas - linkedin Maarten